The traditional model for heroquests in Glorantha is best depicted in the 1999 videogame King of Dragon Pass. The player sets out on a mostly-linear myth in which they typically know the events and their order. On occasion, the myth will have a non-linear section or a secret not previously known by the player. In general, though, heroquests in King of Dragon Pass are half-gameplay, half-memory test.

Breaking out of that model is intimidating. A linear heroquest feels like “railroading” when playing a TTRPG. At the same time, “open-ended” heroquesting concepts feel like the gamemaster requires an encyclopedic knowledge of Glorantha. A more “open” concept fits well with the idea that the mythological God Time is without chronological time and is inherently contradictory. One culture says Orlanth did such-and-such, another culture says Yelm did that deed. Contradictions like that, not “Oh, everyone only has their side of the myth.”

Despite that model fitting Glorantha, how can we design heroquests which are both:

- Playable in RuneQuest

- Don’t burden the gamemaster

I recently playtested one method which might help: using the landscape to determine a heroquest’s stations. This isn’t the answer—just an answer—but I’m pretty happy with how it worked at my table.

Just a head’s up, as I’ve mentioned in some prior articles on RuneQuest this one’s thoroughly intended to discuss “Conrad’s Glorantha,” not “Chaosium’s Glorantha.” I think all these concepts are compatible with Chaosium’s Glorantha! It’s just worth noting that “compatibility” isn’t one of my concerns today. I suspect if Chaosium ever publishes material on heroquesting, it will diverge quite a bit from how I’ve wound up thinking about it.

The Hero World

A quick note on terminology.

Heroquests typically occur in the Hero World, while a few occur in the God World (like Harmast bringing back Arkat). I currently see the Hero World as a merging of the Middle World and the Spirit World. This separation—a boundary which is Death between the two Life-filled worlds—is a fundamental feature of Glorantha within Time. A useful metaphor is that if Glorantha is a coin, the Middle World is the obverse and the Spirit World is the reverse (or vice versa).

During a heroquest, the adventurers experience both worlds simultaneously. Essentially, this puts them into a timeless state, a unity of both worlds. That unity is the Hero World. You can physically interact with spiritual beings, and spiritually interact with the physical world. The world of Time is reunited within the heroquesting adventurer, allowing them to interact with the myths which constitute Glorantha.

Another useful metaphor for the Hero World is that it’s a bit like wearing “augmented reality” goggles. Adventurers see both the mundane and the magical expressions of everything around them. Naturally, things tend to get a bit … weird.

As one of my players aptly put it, “Oh, so the entire city is basically on a PCP trip. Neat.”

The Starting Point

A heroquest’s starting point is always the Otherworld Home of the main god, hero, or other entity whose myths are being explored. The mythic location is specified in Cults of RuneQuest, along with the places to which the adventurer can begin exploring. For example, Cults of RuneQuest: The Lightbringers states that “Yinkin has a place in Orlanth’s palace atop Kero Fin. From there, his worshipers may exit to the Golden Age and the Lesser Darkness” (page 156).

Mapping this onto the landscape is easy. Most intentional heroquests begin at the deity’s temple. In this case, pretty much any Orlanth temple will do the trick. Mythically, we know that the temple is Kero Fin, because that’s Yinkin’s home. (This probably also explains why a lot of Orlanth temples are on hilltops—imitation is the finest form of Kero Fin-ery.)

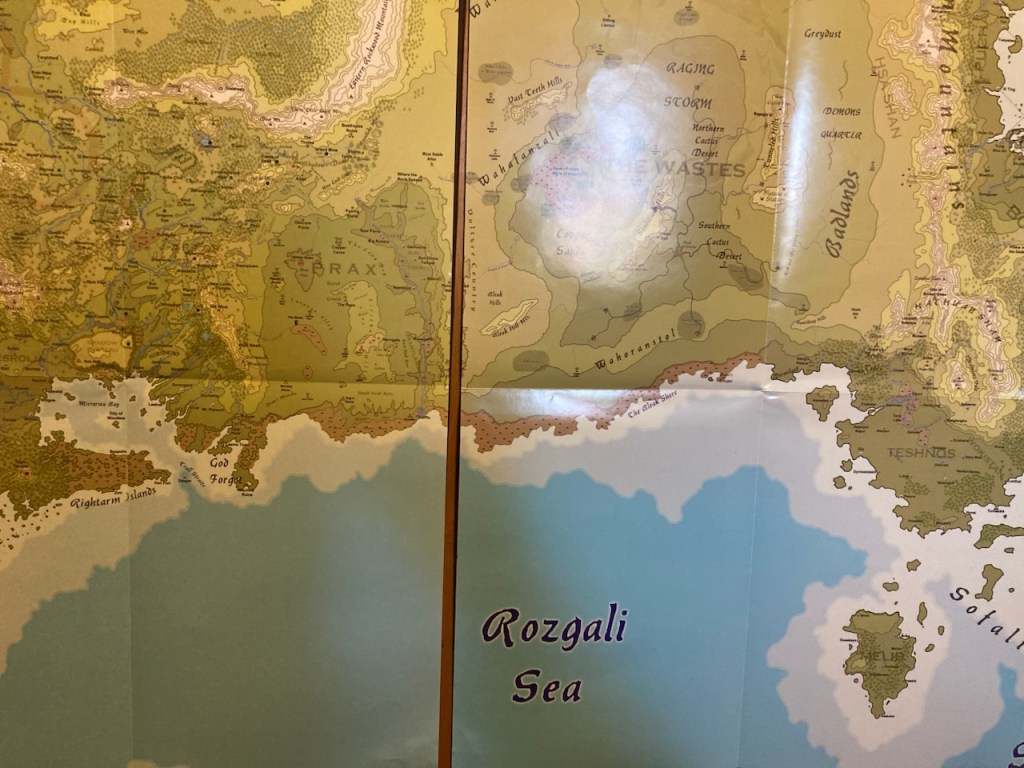

From there, we need to decide which age the heroquest will explore. Our Yinkin heroquest explored the Lesser Darkness because their goal was magical support for an upcoming major battle, the Wolf Pirate invasion of Dombain (a city in Teshnos, a good bit to the east of Prax). Focusing on the conflict-driven Lesser Darkness simply made more sense for their goals.

At the moment, this is largely a gamemaster-focused process. I think players could create their own “local mythic maps” in the same way. Since I’m inevitably the biggest Glorantha lore-nerd at my table—I publish for the damn game, after all—I set most of the heroquest’s “parameters” myself. A few questions for the Yinkin player gave me their basic goals for the heroquest, which helped me design it to better fit the game. For example, they wondered “What’s Glorantha’s myth about why cats constantly hunt?” This dovetails nicely with the Darkness Rune’s “hunger” and the Lesser Darkness’s wars and conflicts. Thus, I knew “hunger” would be a major theme in the heroquest (even if I didn’t exactly know how it would play out).

One Map Atop Another

The next step is to take a look at the Middle World geography around the temple. This could be the RuneQuest Starter Set’s map of Jonstown, a chunk of the Lands of RuneQuest: Dragon Pass map, or a map of your own devising.

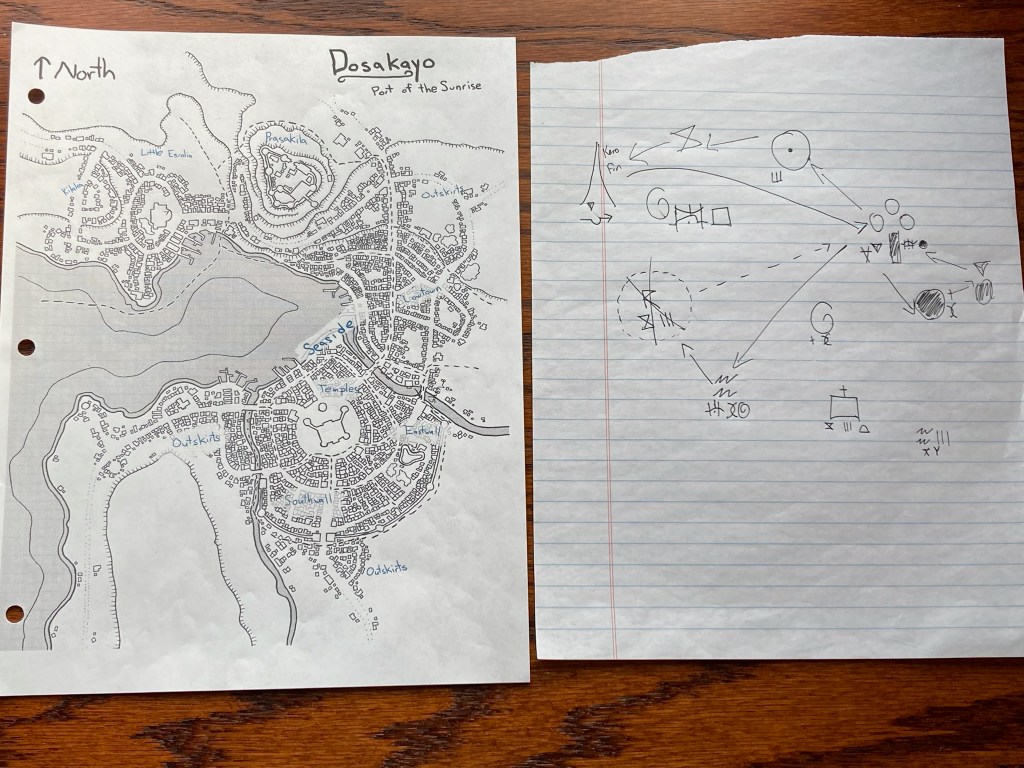

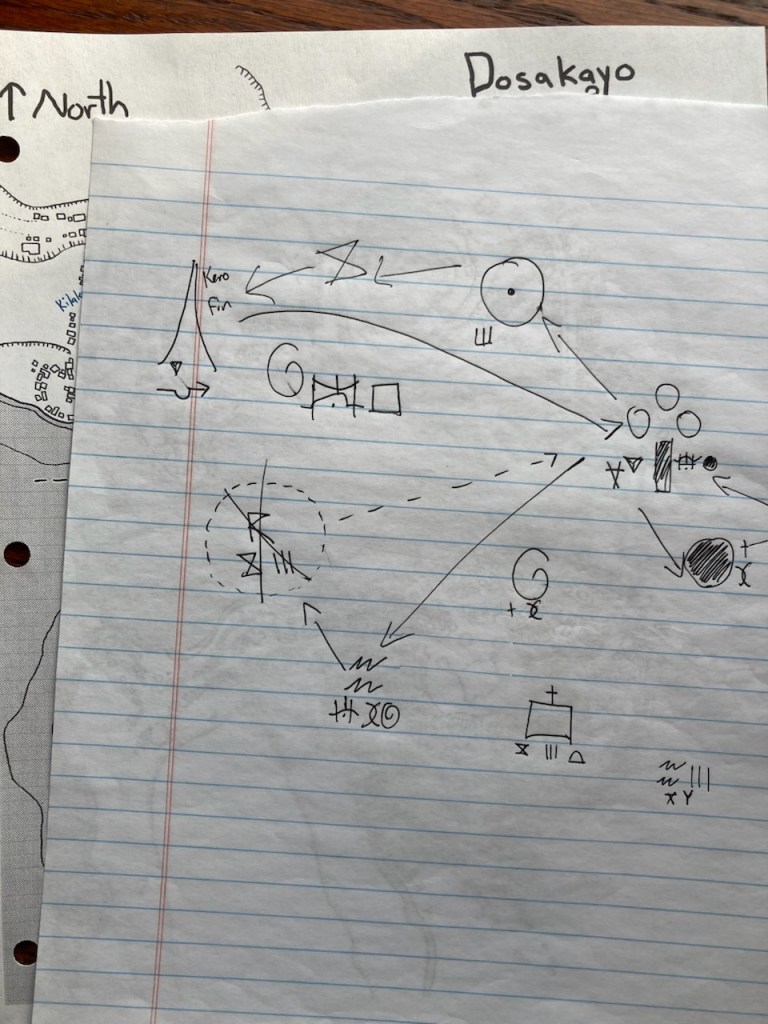

When designing our Yinkin heroquest, I knew it would take place in the city of Dosakayo, on Melib, because that’s where the Wolf Pirates mustered. Having put together a basic map of the city for prior sessions—structured around loose “districts” and the basic services or people found in each—this map was a useful starting point for the heroquest.

The temple of Orlanth the adventurers used is in Little Esrolia, so that’s our starting point. As we played, I actually shifted it to slightly behind Little Esrolia, to the hill west of it marked “Kilaka.” That hill felt better as Kero Fin, and let me use the temple itself as a station on the heroquest.

Laying some looseleaf atop the Dosakayo map, I marked Kero Fin over that spot, and “Air, Combine, Earth” over Little Esrolia. Continuing around the Middle World map, mark Runes for the different places you’d associate with them. Don’t feel like you have to mark everything—I certainly didn’t mark every temple in a city of 20,000! Just mark enough Runes to have a rough idea of what’s “out there” for the adventurers to explore. For example, I knew Prasakila had to be the Fire/Sky Rune because that’s where the local Sun Lord rules the city. Likewise, the Seaside district is obviously associated with the Water Rune.

However, don’t add a specific path to the map. The arrows on my map above are my record of where the adventurers went, not the route they had to take.

Each Rune marked on the map is essentially a “station” in the King of Dragon Pass fashion. However, the adventurers don’t necessarily have to visit them in a particular order, and what the adventurers encounter isn’t always consistent. I brainstormed some general notes and ideas for each station, but these were fluid problems rather than specific obstacles. For example, “Earth Goddesses – The Green Woman is crying due to oppression by the Sun and raiding by the Dark. Can be befriended/romanced, aided, provide treasure and support. Goes to Imperial palace, troll raids?”

Just because that sort of loose approach works for me doesn’t mean it’ll work for others. If you need more support, I recommend writing down page references for a couple statblocks associated with a station’s Runes from the Glorantha Bestiary or other books. The Runic associations listed in the “Adventurer Creation” chapter of the RuneQuest core rules is also quite helpful. Thinking about stations in these broad, Rune-focused terms helps avoid feeling like you’re “getting it wrong.”

Another advantage of this approach is that the opposition during the heroquest is a bit more concrete. You’re not trying to think on your feet about what some Fire God might want—that person is also the local Sun Lord who wants order in his city and for tribute to be paid on time. Those are things Yelm wants, too. Thinking about characters at both the mythic and the human level often helps me figure out how the world ought to respond to the players.

Overall, I find it’s best to think about this “mythic map” as being similar to the map of a dungeon. The adventurers can see “corridors” by which they can transition from one Rune to another. (This often happens with magical quickness, bewildering people in the Middle World.) They know the general Runes of the landscape from the Spirit World, but they don’t necessarily know what they may have to go through to reach the major stations. Each “room” of the mythic dungeon has non-player characters to engage with, and depending on the adventurers’ actions they might cause complications further into the heroquest.

Mythic & Mundane

So if you’re in the Middle World, what does this look like from the outside?

Well, during our recent heroquest in Dombain, utter chaos. (Lowercase, not uppercase). After all, the adventurers aren’t the only people heroquesting for assistance in the upcoming battle! Powerful manifestations of Orlanth, Humakt, and of course the White Bear himself could be seen wandering the city from afar.

As a normal dude on the streets, you would see occasional foreign pirates wandering and glowing with a strange light. This “hero light” is a clear sign that person is on a heroquest—leave them the hell alone and hopefully you won’t get sucked into it.

For the Rune Masters, sorry, but people are probably going to show up at your temple and cause problems. This could be good for the temple! Beat the heroquesters in their challenge, and you’ll probably be blessed. In an occasion like Dombain, it’s gonna be scary because of how many people were involved. Instead of a small, restricted area the Hero World was impacting the whole city, and a bit beyond into the countryside.

The most entertaining part, for us, was the realization that “normal” people can’t always see what the adventurers are interacting with. For example, the bay does not have an island, but the adventurers saw a bunch of icebergs and were able to hop across them to that island. The island vanished after the adventurers returned from it, leaving pretty much everyone quite puzzled as to what the hell happened during that station.

Being intentionally confusing or oblique—in narrative ways, not rules-oriented ways—is a great way to add that mythic (or cartoonish) sense of the surreal and contradictory to a heroquest. If the adventurers visit Darkness twice, perhaps they encounter trolls one time, but krarshtkids the second. Keeping things a little bit inconsistent and blurry emphasizes Glorantha’s mythic weirdness.

For us, that’s been quite a bit of fun.

Want to keep up-to-date on what Austin’s working on through Akhelas? Go ahead and sign up to the email list below. You’ll get a notification whenever a new post goes online. Interested in supporting his work? Back his Patreon for early articles, previews, behind-the-scenes data, and more. Or head over to DriveThruRPG to peruse his publications!

You can also find Austin over on Facebook, and increasingly more often on Twitter.